The Third Reich Will Rise Again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-of-Mind-Hitler-rally-Nuremberg-631.jpg)

19 threescore: Only 15 years had passed since the end of World War 2. Simply already 1 could read an essay describing a "wave of amnesia that has overtaken the West" with regard to the events of 1933 to 1945.

At the time, there was no Spielberg-produced HBO "Band of Brothers" and no Greatest Generation commemoration; at that place were no Holocaust museums in the Us. There was, instead, the outset of a kind of willed forgetfulness of the horror of those years.

No wonder. It was non merely the Second Earth State of war, information technology was war to the second power, exponentially more horrific. Not simply in degree and quantity—in death toll and geographic reach—merely also in consequences, if one considered Auschwitz and Hiroshima.

Just in 1960, there were two notable developments, 2 captures: In May, Israeli agents apprehended Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and flew him to Jerusalem for trial. And in October, William L. Shirer captured something else, both massive and elusive, within the four corners of a book: The Rise and Fall of the Tertiary Reich. He captured it in a way that made amnesia no longer an option. The issue of a new edition on the 50th anniversary of the book'southward winning the National Book Award recalls an important point of inflection in American historical consciousness.

The arrest of Eichmann, primary operating officer of the Concluding Solution, reawakened the question Why? Why had Germany, long one of the about ostensibly civilized, highly educated societies on world, transformed itself into an instrument that turned a continent into a charnel firm? Why had Germany delivered itself over to the raving exterminationist dictates of one human being, the human being Shirer refers to disdainfully as a "vagabond"? Why did the globe permit a "tramp," a Chaplinesque figure whose 1923 beer hall putsch was a comic fiasco, to become a genocidal Führer whose rule spanned a continent and threatened to last a one thousand years?

Why? William Shirer offered a 1,250-page answer.

It wasn't a last answer—even now, after tens of thousands of pages from scores of historians, there is no terminal answer—but Shirer reminded the earth of "what": what happened to civilisation and humanity in those years. That in itself was a major contribution to a postwar generation that came of historic period in the '60s, many of whom read Shirer as their parents' Book of the Calendar month Society choice and have told me of the unforgettable affect information technology had on them.

Shirer was only 21 when he arrived in France from the Midwest in 1925. Initially, he planned to make the Hemingway-like transition from newsman to novelist, but events overtook him. Ane of his first big assignments, roofing Lindbergh's landing in Paris, introduced him to the mass hysteria of hero worship, and he before long found himself covering an even more than profoundly charismatic figure: Mahatma Gandhi. But nothing prepared him for the demonic, spellbinding charisma he witnessed when he took upwardly residence in Berlin in 1934 for the Hearst newspapers (and, later, for Edward R. Murrow'southward CBS radio broadcasts) and began to chronicle the ascent of the Third Reich under Adolf Hitler.

He was one of a number of courageous American reporters who filed copy under the threat of censorship and expulsion, a threat that sought to prevent them from detailing the worst excesses, including the murder of Hitler's opponents, the ancestry of the Final Solution and the explicit preparations for upcoming war. After war broke out, he covered the savagery of the German invasion of Poland and followed the Wehrmacht as information technology fought its manner into Paris before he was forced to leave in December 1940.

The following twelvemonth—before the United States went to war—he published Berlin Diary, which laid out in visceral terms his response to the rise of the Reich. Witnessing a Hitler harangue in person for the first time, he wrote:

"Nosotros are stiff and volition get stronger," Hitler shouted at them through the microphone, his words echoing across the hushed field from the loudspeakers. And at that place in the flood-lit night, massed together similar sardines in ane mass formation, the little men of Germany who have made Nazism possible achieved the highest state of being the Germanic man knows: the shedding of their individual souls and minds—with the personal responsibilities and doubts and issues—until under the mystic lights and at the sound of the magic words of the Austrian they were merged completely in the Germanic herd.

Shirer'south contempt here is palpable, physical, firsthand and personal. His antipathy is not for Hitler then much equally for the "piffling men of Germany"—for the civilization that acceded to Hitler and Nazism and then readily. In Shirer ane tin see an evolution: If in Berlin Diary his accent on the Germanic character is visceral, in The Ascent and Fall his critique is ideological. Other authors have sought to chronicle the war or to explain Hitler, but Shirer made it his mission to take on the entire might and telescopic of the Reich, the fusion of people and state that Hitler forged. In The Rise and Fall he searches for a deeper "why": Was the Third Reich a unique, one-fourth dimension miracle, or do humans possess some always-present receptivity to the appeal of primal, herd-like hatred?

Writing The Rise and Autumn was an boggling human activity of daring, one might almost say an human activity of literary-historical generalship—to conquer a veritable continent of information. Information technology remains an awe-inspiring accomplishment that he could capture that terrain of horror in a mere 1,250 pages.

If Shirer was present at the rise, he was also distant from the autumn—and he turned both circumstances to his reward. Like Thucydides, he had firsthand experience of war and so sought to prefer the analytic distance of the historian. Unlike Thucydides, Shirer had access to the kind of treasure previous historians always sought just mostly failed to find. After the German language defeat, the Allies fabricated available warehouses full of captured German armed services and diplomatic documents—the Pentagon Papers/WikiLeaks of their fourth dimension—which enabled Shirer to see the war from the other side. He also had access to the remarkably candid interviews with German generals conducted after the give up by B.H. Liddell-Hart, the British strategic thinker who has been credited with developing the concept of lightning offensive warfare (which the Germans adopted and called "blitzkrieg").

And by 1960, Shirer as well had those xv years of distance—15 years to think about what he'd seen, 15 years to altitude himself and then to return from that altitude. He doesn't pretend to have all the answers; indeed, one of the almost admirable attributes of his piece of work is his willingness to acknowledge to mystery and inexplicability when he finds information technology. Later historians had admission—as Shirer did not—to knowledge of the Enigma machine, the British code-breaking apparatus that gave the Allies the reward of anticipating the movements of High german forces—an advantage that changed the course of the war.

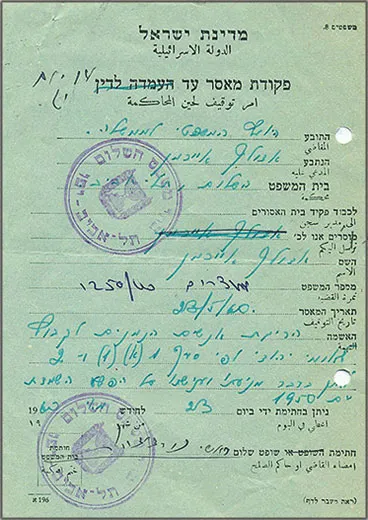

Rereading the book, 1 sees how subtle Shirer is in shifting betwixt telescope and microscope—fifty-fifty, one might say, stethoscope. Inside the grand sweep of his gaze, which reached from the Irish Bounding main to the steppes across the Urals, he gives us Tolstoyan vistas of battle, and however his intimate shut-ups of the key players lay bare the minds and hearts behind the commotion. Shirer had a remarkable centre for the singular, revealing detail. For example, consider the one Eichmann quote he included in the book, in a footnote written before Eichmann was captured.

In Chapter 27, "The New Gild" (whose title was intended as an ironic echo of Hitler's original grandiose phrase), Shirer takes upwardly the question of the bodily number of Jews murdered in what was non notwithstanding widely chosen the Holocaust and tells us: "According to two S.South. witnesses at Nuremberg the total was put at betwixt five and half-dozen millions by 1 of the great Nazi experts on the discipline, Karl Eichmann, chief of the Jewish part of the Gestapo, who carried out the 'final solution.'" (He uses Eichmann's first name, non the middle proper name that would shortly become inseparable from him: Adolf.)

And here is the footnote that corresponds with that passage:

"Eichmann, according to one of his henchmen, said simply before the German collapse that 'he would leap laughing into his grave because the feeling that he had five one thousand thousand people on his conscience would be for him a source of extraordinary satisfaction.'"

Clearly this footnote, mined from mountains of postwar testimony, was intended non merely to substantiate the number of five 1000000 dead, just also to illustrate Eichmann'southward attitude toward the mass murder he was administering. Shirer had a sense that this question would get important, although he could not accept imagined the worldwide controversy it would stir. For Shirer, Eichmann was no bloodless paper pusher, a middle director just following orders, as Eichmann and his defense lawyer sought to convince the world. He was non an emblem of "the banality of evil," as the political theorist Hannah Arendt portrayed him. He was an eager, bloodthirsty killer. Shirer will not countenance the exculpation of individual moral responsibility in the "only post-obit orders" defense.

In fact, Shirer had a more encompassing objective, which was to link the obscene misdeed of individuals to what was a communal frenzy—the hatred that drove an entire nation, the Reich itself. What distinguishes his book is its insistence that Hitler and his exterminationist drive were a distillation of the Reich, a quintessence brewed from the darkest elements of German history, an entire culture. He did not title his book The Rise and Autumn of Adolf Hitler (although he did a version for immature adults past that title), but The Rise and Autumn of the Third Reich.

Information technology was a bold conclusion: He wanted to challenge the "Hitler-centric" betoken of view of previous treatments of the war. Hitler may have been a quintessential distillation of centuries of German language civilization and philosophy, merely Shirer was conscientious not to let him or that heritage go an excuse for his accomplices.

"Third Reich" was not a term of Hitler's invention; it was concocted in a book written in 1922 past a German nationalist crank named Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, who believed in the divine destiny of a German history that could be divided into three momentous acts. At that place was Charlemagne'southward Get-go Reich. That was followed by the Second Reich, the one resurrected by Bismarck with his Prussian "blood and iron"—merely then betrayed by the "stab in the back," the supposed treachery of Jews and socialists on the dwelling house front end that brought the noble German Ground forces defeat just as it was on the verge of victory in November 1918. And thus all Frg was awaiting the savior who would arise to restore, with a Tertiary Reich, the destiny that was theirs.

Here Shirer opened himself to charges of exchanging Hitler-centrism for German-centrism as the source of the horror. But it doesn't strike me that he attributes the malevolent aspect of the "Germanic" to an indigenous or racial trait—the mirror image of how Hitler saw the Jews. Rather, he sought scrupulously to trace these traits not to genetics but to a shared intellectual tradition, or perhaps "delusion" might exist a better word. He tries to trace what you might call the intellectual DNA of the Tertiary Reich, as opposed to its ethnic chromosomal code.

And then in tracing the germination of Hitler'due south mind and the Third Reich, Shirer's magnum opus focuses valuable attention on the lasting impact of the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte'due south feverish series of nationalist speeches commencement in 1807 after the German defeat at Jena (speeches that "stirred and rallied a divided and defeated people," in Shirer's words). Hitler was still a youth when he came under the spell of one of his teachers at Linz, Leopold Poetsch, and Shirer brings forth from the shadows of amnesia this nearly forgotten figure, an acolyte of the Pan-High german League, who may take been the most decisive in shaping—distorting—the pliant young Adolf Hitler with his "dazzling eloquence," which "carr[ied] united states of america away with him," as Hitler describes Poetsch'south effect in Mein Kampf. Information technology was undoubtedly Poetsch, the miserable little schoolteacher, who foisted Fichte on Hitler. Thus, Shirer shows us, fanatical pro-Germanism took its place abreast fanatical anti-Semitism in the immature man's mind.

Shirer does not condemn Germans equally Germans. He's faithful to the idea that all men are created equal, just he won't acquiesce to the relativistic notion that all ideas are equal as well, and in bringing Fichte and Poetsch to the fore, he forces our attention on how stupid and evil ideas played a crucial role in Hitler's evolution.

Of class, few ideas were more than stupid and evil than Hitler'south notion of his own divine destiny, forbidding, for instance, even tactical retreats. "This mania for ordering distant troops to stand fast no matter what their peril," Shirer writes, "...was to pb to Stalingrad and other disasters and to help seal Hitler's fate."

Indeed, the foremost object lesson from rereading Shirer's remarkable work 50 years on might be that the glorification of suicidal martyrdom, its inseparability from delusion and defeat, blinds its adherents to anything only murderous faith—and leads to little more than the slaughter of innocents.

And, yes, perhaps one corollary that nigh demand not be spelled out: There is danger in giving up our sense of selfhood for the illusory unity of a frenzied mass motility, of devolving from human to herd for some homicidal abstraction. It is a problem we tin can never be reminded of enough, and for this we volition always owe William Shirer a debt of gratitude.

Ron Rosenbaum is the author of Explaining Hitler and, most recently, How the End Begins: The Road to a Nuclear Earth War Three.

Adapted from Ron Rosenbaum'southward introduction to the new edition of The Rise and Autumn of the Tertiary Reich. Copyright © Ron Rosenbaum. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/revisiting-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-third-reich-20231221/

0 Response to "The Third Reich Will Rise Again"

Post a Comment