Review the Concept of Evidence-based Public Health Strategies

Abstract

Background

Sustainability of evidence-based interventions (EBI) remains a challenge for public wellness community-based institutions. The conceptual definition of sustainment is not universally agreed upon by researchers and practitioners, and strategies utilized to facilitate sustainment of EBI are not consistently reported in published literature. Given these limitations in the field, a systematic review was conducted to summarize the existing evidence supporting discrete sustainment strategies for public health EBIs and facilitating and hindering factors of sustainment.

Methods

We searched PsychINFO, Embase, ProQuest, PubMed, and Google Scholar. The initial search was run in March 2017 and an update was done in March 2019. Written report eligibility criteria included (a) public wellness evidence-based interventions, (b) conducted in the community or community-based settings, and (c) reported outcomes related to EBI sustainment. Details characterizing the study setting, design, target population, and type of EBI sustained were extracted.

Results

A total of 26 manufactures published from 2004 to 2019 were eligible for data extraction. Overall, the importance of sustainability was acknowledged across all of the studies. However, simply vii studies presented a conceptual definition of sustainment explicitly within the text. Six of the included studies reported specific sustainment strategies that were used to facilitate the sustainment of EBI. Only three of the studies reported their activities related to sustainment by referencing a sustainment framework. Multiple facilitators (i.e., accommodation/alignment, funding) and barriers (i.e., limited funding, express resources) were identified equally influencing EBI sustainment. The majority (n = 20) of the studies were conducted in high-income countries. Studies from low-income countries were by and large naturalistic. All of the studies from low-income countries reported lack of funding equally a hindrance to sustainment.

Implication for dissemination and implementation research

Literature focused on sustainment of public health EBIs should present an explicit definition of the concept. Better reporting of the framework utilized, steps followed, and adaptations fabricated to sustain the intervention might contribute to standardizing and developing the concept. Moreover, encouraging longitudinal dissemination and implementation (D&I) research especially in low-income countries might assist strengthen D&I research capacity in public health settings.

Groundwork

Sustaining the changes that consequence from bear witness-based public health interventions has become a topic of great interest among many researchers, donors, practitioners, and communities [1]. Show-based interventions (EBI) are divers as practices by which the provider'southward decision is backed by the most appropriate information [2]. EBIs originated from the evidence-based medicine motion. In recent years, additional fields that involve routine intervention and clinical decision making have embraced this movement [3]. This includes a range of EBIs in treatment research, prevention, policy, medicine, community-based public health, and overall healthcare [iv,five,6,7]. Although EBIs are conceptually highly-seasoned, our agreement of the implementation processes, including sustainment, that are necessary for delivering these practices over time in community-based settings remains unclear [i]. The field of dissemination and implementation (D&I) science has provided definitions for conceptually distinct terms, sustainability, and sustainment. Sustainability is defined as "the extent to which an evidence-based intervention can deliver its intended benefits over an extended period of time after external support… is terminated" [8] (p. 26), whereas sustainment is defined as "creating and supporting the structures and processes that will let an implemented innovation to be maintained in a system or organisation" [ix].

Research-to-practice gap

The past few decades have marked a meaning shift from traditional diffusion of interventions and research outcomes—"passive, untargeted, unplanned, and uncontrolled spread of new interventions" [10]—to a more than structured arroyo of EBI broadcasting, implementation, and sustainment in order to reduce the oft-noted research-to-practice gap [11]. Current estimates suggest that it takes about 17 years to implement only 14% of prove-based enquiry outcomes in real-world settings [12, 13]. This research-to-practice gap often translates to suboptimal care for patients, exposure to potentially avoidable harm, excessive healthcare spending, and other significant opportunity costs [14]. Multiple and mutually interacting factors are believed to contribute to this big research translation gap. Previous studies report that inadequate training, limited time, lack of infrastructure, and lack of feedback and incentives for the utilization of EBIs hinder timely adoption and sustainment of EBIs in real-world settings [fifteen]. Farther, of the EBIs that are adopted and implemented, many EBIs are not sustained after a sure amount of time [15].

Public health evidence-based interventions

Traditionally, the goal of intervention developers is to test the efficacy of the novel intervention in ideal settings with ideal participants and practitioners; however, this is not the typical end-point for public health researchers. For instance, effectiveness inquiry focuses on testing an individual-level intervention that is being delivered inside "real-world" settings past usual intendance providers to community patients. The outcome measures still remain at the individual or family level [eight]. Still, sustainment of EBIs within customs-based organizations requires the evaluation of the processes and factors that may facilitate or hinder the continuation of an EBI [nine]. For example, the field of health organization quality improvement emphasizes the comparative cess of the value of organizational or organization-level interventions that back up the sustainability of EBIs [16]. Thus, careful planning is necessary to ensure swift and sustained applications of findings from show-based enquiry into real-world settings [17]. Implementation studies in public health have emphasized the importance of developing sustainability strategies throughout the planning phase of an EBI to achieve its utmost benefits at the individual, client, and organizational level [18]. Yet, the sustainment of EBIs in community-based settings remains a major challenge [19].

In the past few years, sustainability has been a buzz word in various disciplines, including public health research. Despite its appeal, the concept has remained undefined or loosely divers in almost public health research, leading to underreported or vague findings [20]. The ambiguity in the conceptual and operational definition of sustainment has been identified equally one of the barriers contributing to the large translational gap in public health and healthcare in general [21].

Sustainment of EBIs presents many complexities. While planning for the sustainment of EBIs, researchers and practitioners oft face different unanticipated challenges pertaining to intervention characteristics, the organizational setting, and the broader policy surroundings [22]. For example, past overcoming these inner and outer contextual challenges, some public wellness interventions take been successfully sustained with fidelity. Yet, other EBIs may require adaptations over time to continue to work effectively in a complicated and dynamic real-world context [23, 24]. Effective sustainment strategies, outside of fidelity monitoring, for adapted interventions, are not well reported upon in implementation studies.

Sustainment efforts in low- and middle-income countries

Challenges to implementing EBIs in communities inside the US also bear over to low-income countries, where cultural differences, barriers to cost, accessibility and quality are mutual. Given these barriers in adoption and broadcasting of EBIs in low-income countries, sustaining any programme efforts remains hard [25].

The limited evidence from depression- and eye-income countries (LMICs) reported that complexity of the intervention and inadequate program familiarity, limited man resources, and lack of workplace support for the new program and high staff turnover every bit barriers to sustainment [26,27,28]. Moreover, express wellness organisation capacity, poor awarding of show-based interventions, inadequate involvement of local implementers, and loftier staff turnover besides were reported to hinder the use of public health EBIs [28]. Yet, express evidence exists regarding the sustainment of EBIs in LMICs compared to high-income countries (HICs) [29]. The broader factors influencing the sustainment of EBIs in these settings remain underreported.

Given that little is known about how and nether what conditions sustainability occurs, it remains unclear equally to what strategies facilitate or hinder sustainability outcomes [thirty]. For instance, strategies to facilitate maintenance of wellness benefits activities or workforce capacity take non been recognized considering of the limited understanding to the developing procedure of sustainability [31, 32]. Therefore, in that location is a demand to identify and draw existing facilitators or barriers to sustainment outcomes to meliorate understand implementation processes, promote the use of impactful EBIs, and advance the field of dissemination and implementation science.

Objectives

The goal of this systematic review was to understand the state of the literature related to the sustainment of public health EBIs. Specifically, nosotros aimed to (1) describe how sustainability was divers; (2) identify and depict evidence-based sustainment strategies utilized in peer-reviewed public health literature; (iii) identify methods for evaluating sustainment outcomes; (iv) identify sustainment strategies utilized and with which specific stakeholder groups; (five) identify and describe reported sustainment outcomes; (half dozen) develop recommendations for (a) reporting sustainment efforts as well as (b) utilizing specific sustainment strategies with specific stakeholder groups, both initially and when sustainment seems to be failing; and (vii) sustainment efforts in depression -income settings.

Methods

Methods for the systematic followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline. We specified the methods in advance and documented every stride in an a priori protocol. The protocol was updated iteratively throughout the systematic review (the systematic review protocol is available upon asking from the first author).

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies included articles that (1) were peer-reviewed, (two) written in the English linguistic communication, (3) reported the use of a specific EBI, (4) involved the implementation of an EBI in a community-based setting, and (five) provided a description of strategies used to sustain the EBI. Our search was not restricted to specific population or year of publication. Nosotros excluded articles that were (i) not based on original information, (two) generic reports that did not focus on a specific EBI, or (3) reviews of other published or unpublished prove. We did not include unpublished (ongoing) studies because these were not available on the databases we searched.

Data sources

Multiple electronic database indexes were searched for potentially eligible articles, including PsycINFO (1887–present), ProQuest including ERIC and CSA social sciences' abstracts (1971–present), PubMed (1946–present), Embase (1976-present), and Google Scholar (2004–present). Further, experts in the area of EBI sustainment were contacted by the senior author and asked to propose additional relevant articles that had not been included. Finally, reference lists of identified articles (including systematic reviews) were checked for potentially eligible articles. Duplicate articles were excluded at each stage of the search process. Nosotros conducted an initial search in March 2017, and additional time-restricted searches (March 2017–March 2019) were run to identify more recently published studies.

Search strategy

The post-obit keywords were searched in any combination: "sustainment," "sustainability," "scale-up," "continuation," "health," "providers," "community," "policy," "services," and "interventions." These search terms were identified during a preliminary search of the literature focused on discovering the various terms used in articles related to the sustainment of EBIs. A filter was used in all searches to exclude review manufactures, manufactures in other languages, or articles that are non peer-reviewed.

Report selection

The first and second authors reviewed the titles and abstracts identified by the searches. Articles were eligible for the total-text review if the title or abstract referenced equally follows: (1) utilize of any specified EBI, (2) if the EBI was delivered in a community-based arrangement, and (3) provided a description of sustainment procedure. If project members could not decide initial eligibility from the championship and abstract, the article passed to the next stage for a total-text review. Articles were excluded if the title and abstract did not pertain to EBI sustainment.

Two project members independently reviewed all of 4892 titles screened for inclusion. Inter-rater agreement for inclusion between the independent coders was 86%. Disagreements betwixt reviewers were resolved with discussions aimed to develop a consensus almost the eligibility of studies, with consultation from other co-authors, as needed.

Later the title and abstract review, members of the coding team were randomly assigned manufactures (10–15 articles each) to review. Two project members independently reviewed the full-text of each commodity to determine inclusion into or exclusion from the systematic review. Disagreements were resolved through discussion betwixt the two reviewers and a third independent reviewer until consensus was reached.

Information drove process

A information extraction course containing an initial coding scheme was adult a priori, based on the written report objectives and preliminary conceptualizations of sustainment strategies. Boosted codes were generated deductively past the data extraction team, which consisted of four reviewers. Training for the reviewers included a half-day didactic coding workshop involving an introduction to the PRISMA statement [33] and discussion of each variable definition using exercise articles. Raters reconvened to review how a second practice article was independently rated by each of the reviewers and to resolve any discrepancies or ambiguities about the coding process. All raters were asked to independently code and review iv additional articles to ensure clarity of the variables and consistency in the coding process. Raters were provided coding documents containing assignment sheets, training slides and notes, the survey, variable operational definitions, and printed articles for review. Twelve consensus meetings were held during the initial full-text review. The coding template was farther refined for the side by side level of the review. The new template was pilot-tested with x% of the manufactures, discussed, and endorsed to be used for the last total-text review. Additional ten consensus meetings were held for the final full-text review.

Data items

The extracted data comprised of 45 items focusing on (1) basic publication details almost the article (i.e., publication date, author), (2) study blueprint and methods, (3) reported EBI outcomes, (4) sustainment strategies, (five) targeted audience of sustainment strategies (e.g., organizational leaders, straight providers), (6) barriers and facilitators influencing sustainment outcomes, and (7) miscellaneous details on funding and comments/concerns about the articles. Data about the data items is available in the systematic review protocol.

Risk of bias

To establish the forcefulness of the body of evidence, we evaluated the risk of bias in individual studies and across studies. In individual studies, we checked validity and reliability of the measures used, report setting, appropriateness of the study pattern, methods of data collection, and how these interacted with reporting and outcomes [34]. We did non restrict our search to outcomes (positive/negative) to minimize the possibility of publication bias [35].

Data assay

All of the articles were independently double-coded by pairs of raters. Whenever disagreements emerged, the group of coders met to discuss coding disagreements until consensus was reached. All data were collected using the Qualtrics online survey programme [36]. Raters received a link to the online survey via email. All coding was starting time conducted on printed articles and then entered into the online survey to create the database. Data were after exported to SPSS V.14 [37] for analysis. The review team (MH, TB, RB, and BM) met to discuss emerging themes and to create a reporting structure based on the objectives of the report. Recurrent themes that were identified were thematically categorized to facilitate reporting. Moreover, we also compared studies from high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Results

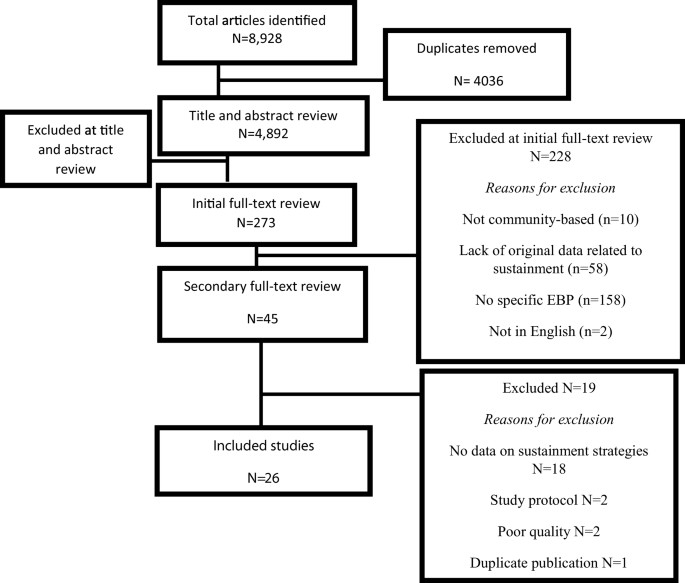

Report choice

Searches generated 4892 articles published up to March 2019 (Fig. ane). After reviewing these articles' titles and abstracts, 274 manufactures were determined to see the criteria for a full-text review. After the initial full-text review, 45 articles met the criteria for terminal inclusion. During data extraction, 19 manufactures were excluded considering they did not fit the criteria of containing original data about sustainment strategies (n = 17) or because they were a study protocol or conceptual newspaper (n = 2), were of poor quality based on analysis of rigor and risk of bias (n = 2), or were a duplicate publication (northward = 1).

Flow chart of the study

Characteristics of the studies

A full of 26 manufactures published from 2004 to 2019 were included in the concluding assay. The report settings include wellness intendance facilities (north = 7), other customs-based organizations (n = 6), and communities (northward = 13). The EBIs beingness sustained covered a diversity of topics including physical health, behavioral health, prevention services, and life skills (Table 1).

Quality of included studies

We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [38] to evaluate the quality of cross-sectional studies and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline [39] for appraisement of RCTs. Overall, the studies included in this review rated from moderate to high. Written report design, objectives, and sampling were clearly presented in all of the studies.

Conceptualization of sustainability

In all of the studies, the importance of sustainability was acknowledged. Nevertheless, only x out of the 26 studies included an explicit definition of sustainability. For 16 of the 26 studies, sustainability was inadequately defined or was missing altogether. Specifically, these studies discussed outcomes and influences of sustainability without an explicit definition of sustainability referenced in the text. We reviewed the report objectives of these sixteen studies to determine how sustainability was conceptualized. In 17 of the studies, sustainability was conceptualized in relation to the continuity of a program sustained later the implementation phase. The concept of sustainability in these studies varied; yet, nosotros mapped these conceptualizations onto a consolidated list of definitions developed by Moore and colleagues [forty] (see Table 2).

The following provide examples of the variability in sustainment conceptualization across studies:

In the field of public health, sustainability has been divers as the capacity to maintain plan services at a level that will provide ongoing prevention and treatment for a health problem later on the termination of major financial, managerial, and technical assistance from an external donor. [41]

Another study used the definition of sustainability from Glasgow [42] at the individual and organizational level.

At the individual level, sustainability has been defined every bit the long-term effects of a plan every bit assessed after 6 or more months following the almost contempo intervention contact. [43]

Further, a study from Ghana defined sustainability as the "continuation of benefits" [44]. While another report [45] conceptualized sustainment in terms of retaining the human capacity of service providers and service users:

… a program is sustained if information technology continues to employ staff, maintains an active client caseload, and provides straight services. Programs sometimes continue in proper name only, without adhering to the plan model that they originally implemented. [45]

Specific efforts focusing on sustainment

Of the 26 studies included, vi studies [9, 46,47,48,49,50] reported purposefully building sustainment efforts into the EBI implementation. These studies reported the initiatives they took to ensure the sustainment of the program outcomes after the end of the implementation phase. Further, only five studies reported the utilise of a specific dissemination and implementation framework that guided the sustainment efforts (Tabular array 3). Notably, the remaining 21 studies described their sustainment activities without making any reference to a known a priori theoretical model or framework.

Sustainment strategies used

Sustainment strategies extracted for the systematic review were guided past the conceptual model of factors that influence the sustainment of EBIs [3]. Nine sustainment strategies were identified among the 26 articles (Table iv). Funding and/or contracting for EBIs connected employ (n = 12) and maintenance of workforce skills through continued training, booster preparation sessions, supervision, and feedback (n = nine) were near ofttimes reported. Other sustainment strategies included organizational leader stakeholder prioritizing and supporting continued utilise (n = half-dozen), agency priorities, and/or plan needs are aligned with new EBI (n = iv), maintenance of staff buy-in (n = 3), accessing new or existing coin to facilitate sustainment (northward = 2), systematic adaptation of the EBI to increase continued fit/compatibility of the EBI with the organization (n = eight), mutual accommodation between the EBI and organisation (due east.chiliad., adaptation of the EBI to meliorate fit and alignment of the organizations' procedures) (north = vii), and monitoring EBI effectiveness (northward = ii). Ii of the remaining studies reported that a specific sustainment strategy was not used, and the final three studies described utilizing "positive implementation climate" and "community engagement/partnerships" as sustainment strategies.

Sustainment strategies and stakeholder groups

Of the 26 articles, merely 9 studies [46,47,48,49,fifty,51,52,53,54] provided information nigh the specific intended audition (east.g., stakeholder groups) of the sustainment efforts. Intended audiences for EBI sustainment efforts included direct providers (n = 6), supervisors of straight providers (n = 4), organizational leaders (n = v), and service users (due north = 3) (Table 5). No studies targeted policy-makers in their sustainment efforts.

Sustainment outcomes

Moreover, the nine manufactures that reported specific intended audiences for their sustainment efforts as well provided details on outcomes related to their sustainment strategy utilize. These details were grouped into two categories: (1) sustainment outcomes related to the implementation process and (two) sustainability outcomes directly related to the EBI. For the first category, details on sustainment outcomes included the moderating part of leadership styles (n = 1), the importance of tracking program activities to ensure continued use (n = 1), increased rates in initial and connected employ of the EBIs (northward = iii), and assessments related to degrees of institutionalization of EBIs (n = 1). Sustainability outcomes straight related to the EBI included increased usage of EBI components maintained over time (n = ii) and increased individual-level outcomes (e.g., asthma medication use and education) from EBI utilize (n = one).

Facilitating and hindering factors of EBI sustainment

Twenty-half-dozen facilitating and 23 hindering factors were reported to be of influence on the sustainment of EBIs (Table 6). Utilizing the influences on sustainability framework [20], nosotros mapped each reported facilitator and hindrance onto the framework, which proposes 4 major thematic areas, including (1) innovation characteristics, (two) context, (3) capacity, and (4) processes and interactions. Funding (n = 16), accommodation/alignment (north = fifteen) and organizational leadership (north = 12) were the near oftentimes reported facilitating factors for EBI sustainment. No or express funding (n = 13) was the near frequently reported hindering factor for EBI sustainment.

Studies from LMICs

Of the eligible studies, only five of them [44, 46, 55,56,57] were conducted in LMICs according to the World Bank classification of countries [58]. 1 study did non report the study setting. All of these studies from LMICs followed a naturalistic approach with no longitudinal or RCT design reported. All but one [46] of the studies from LMICs was conducted in a facility-based setting. Regarding barriers to sustainment, all of the studies from LMICs reported that EBIs were non sustained afterward the termination of funding. Moreover, no study from LMICs reported actual targets of sustainment strategies.

Discussion

There is a growing interest to assess sustainment to promote EBIs in public health research. Despite this emerging emphasis, there remains a large research-to-practise gap [12, 13] that can be attributed to inconsistent definitions and underreporting of sustainability. To help address these gaps, this systematic review provides a detailed summary of the current evidence of sustainability in public health interventions across diverse customs-based settings and populations. To our knowledge, this is the showtime comprehensive systematic review that summarized definitions of sustainment and evidence-based intervention sustainment strategies targeting specific audiences inside public wellness literature.

Although the importance of sustainability was acknowledged across all the studies, the concept was inadequately divers with only seven studies presenting a definition of sustainability somewhere in the text. Merely nine of the included studies reported their sustainment efforts [9, 46,47,48,49,50]. Fifty-fifty fewer studies [nine, 46, 47, 52, 53] presented their activities related to sustainment by referencing a known sustainment framework.

Testify exists that various public health interventions are successfully implemented in bookish settings. Nevertheless, ensuring their transferability to community settings or customs-based organizations while besides maintaining fidelity has been a challenge [59, 60]. This claiming could be attributable to a lack of clarity or knowledge about the appropriate frameworks and the steps followed towards the sustainability of the intervention [61]. Consequent with these findings, in our systematic review, but five studies [9, 46, 47, 52, 53] reported a pre-existing framework used to ensure the sustainment of the EBI. Our findings support that studies evaluating sustainment strategies are limited. Therefore, information technology is believed that this underreporting may even farther lengthen the research-practice gap.

Understanding factors related to the implementation of prove-based public wellness interventions has been of significant scholarly attention in recent years [23, 62,63,64]. Yet, lack of proper conceptualization of sustainment from the outset seems to accept bandage a shadow over farther evolution of the field. In majorities of the included studies, sustainment was equated with the continuation of a program or an intervention later on a divers period of fourth dimension [9, 43, 44, 49,fifty,51,52,53]. Although sustainment is widely best-selling as relevant, consequent with what was reported earlier [20], efforts to explicitly define the concept take been found minimal in this systematic review, with only vii studies presenting a definition of sustainability somewhere in the text. This review underscores the apparent need for including a clear and unequivocal definition of the concept of sustainment in the context of public health evidence-based interventions.

Previous studies have identified multiple hindering factors to the sustainment of EBIs in customs-based settings. These include lack of funding, leadership challenges, unfavorable organizational climate, nature of the EBI, inadequate technical assistance, and fidelity monitoring [65, 66]. In this systematic review, 19 studies reported hindering factors related to the sustainment of EBIs. The challenges reported in those studies were also consistent with what was previously reported. Integrating a born machinery to accost leadership challenges and tailoring technical help to provide community stakeholders with the tools to adapt EBIs with or without the EBI developers may be relevant. Moreover, equipping community-based organizations with the skills to identify potential funding sources that can support the continuation of the plan after a certain flow might exist important for sustaining EBIs in these settings.

No RCTs or studies with the longitudinal blueprint were identified from low-income countries. At that place remains a need for more knowledge regarding sustainment efforts of EBIs across LMICs. In part, this could be attributable to the expensive nature of designing and conducting RCTs in resource-constrained settings. Most LMICs generally have express primary research, and most evidence-based interventions are resources intensive, requiring structural and financial provisions [67].

Limitations

While the reported results carry important implications for public health enquiry, we should consider limitations to our systematic review. The review only included studies of sustainability published in peer-reviewed literature. "Gray literature" and unpublished literature were excluded, presenting potential publication bias. We only reviewed studies focused on public health interventions. Studies related to contexts outside of public health interventions were not included, potentially overlooking further details to inform the concept of sustainability. Hereafter inquiry should consider reporting the sustainment of EBIs in settings outside public health interventions.

Conclusions

Studies reporting sustainment-related outcomes might benefit from presenting an explicit definition of the concept from the commencement. Amend reporting of the steps followed, frameworks used and adaptations made to sustain the intervention might contribute to standardizing and developing the concept. Moreover, encouraging longitudinal D&I research specially in low-income countries might help strengthen D&I inquiry capacity in these settings.

Availability of data and materials

Systematic review protocol is available from the first author up on request.

Abbreviations

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- D&I:

-

Dissemination and implementation

- EBI:

-

Evidence-based interventions

- HIC:

-

High-income countries

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

References

-

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based do implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38(one):iv–23.

-

McKibbon K. Bear witness-based practice. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998;86(3):396.

-

Berth A. Evidence based exercise. In: Handbook of library training practice and development: book three, vol. 335; 2012.

-

Victora CG, Habicht J-P, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(three):400–v.

-

Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Stamatakis KA. Understanding evidence-based public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1576–83.

-

Rychetnik L, Hawe P, Waters E, Barratt A, Frommer Chiliad. A glossary for show based public wellness. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(7):538–45.

-

Kohatsu ND, Robinson JG, Torner JC. Evidence-based public health: an evolving concept. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(v):417–21.

-

Rabin BA, Brownson RC. Terminology for dissemination and implementation research, Dissemination and implementation inquiry in health: translating scientific discipline to practice, vol. two; 2017. p. 19–45.

-

Aarons GA, Greenish AE, Trott E, Willging CE, Torres EM, Ehrhart MG, Roesch SC. The roles of organisation and organizational leadership in arrangement-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: a mixed-method written report. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2016;43(6):991–1008.

-

Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Kreuter MW, Weaver NL. A glossary for dissemination and implementation enquiry in health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):117–23.

-

Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust. 2004;180(6 Suppl):S57.

-

Balas EA, Boren SA: Managing clinical cognition for health care comeback. Yearbook of medical informatics 2000: patient-centered systems 2000.

-

Green LW, Glasgow RE, Atkins D, Stange 1000. Making show from research more relevant, useful, and actionable in policy, program planning, and practice: slips "twixt cup and lip". Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(half-dozen):S187–91.

-

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Cognition translation of enquiry findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7(one):fifty.

-

Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus Ac. Why don't we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–7.

-

Doyle C, Howe C, Woodcock T, Myron R, Phekoo K, McNicholas C, Saffer J, Bell D. Making alter last: applying the NHS institute for innovation and improvement sustainability model to healthcare comeback. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):127.

-

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(three):327–fifty.

-

Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis J-50. Making public health programs terminal: conceptualizing sustainability. Eval Program Plann. 2004;27(2):121–33.

-

MacDonald M, Pauly B, Wong G, Schick-Makaroff Thou, van Roode T, Strosher HW, Kothari A, Valaitis R, Manson H, O'Briain W. Supporting successful implementation of public wellness interventions: protocol for a realist synthesis. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):54.

-

Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future enquiry. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):17.

-

Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public wellness and wellness care. Annu Rev Public Wellness. 2018;39:55–76.

-

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation scientific discipline. Implement Sci. 2009;iv(1):50.

-

Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(eleven):2059–67.

-

Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):117.

-

Salinas-Miranda AA, Storch EA, Nelson R, Evans-Baltodano C. Challenges for evidence-based care for children with developmental delays in Nicaragua. J Cogn Psychother. 2014;28(3):226–37.

-

Hodge LM, Turner KM. Sustained implementation of prove-based programs in disadvantaged communities: a conceptual framework of supporting factors. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;58(1–ii):192–210.

-

Gwatkin DR. IMCI: what tin nosotros learn from an innovation that didn't reach the poor? In: SciELO Public Wellness; 2006.

-

Yamey G. What are the barriers to scaling upwards health interventions in depression and center income countries? A qualitative study of academic leaders in implementation scientific discipline. Glob Health. 2012;eight(1):11.

-

Santmyire A. Challenges of implementing show-based practice in the developing world. J Nurse Pract. 2013;9(5):306–11.

-

Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, McMillen C, Brownson R, McCrary S, Padek M. Sustainability of prove-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci. 2015;ten(one):88.

-

Lennox 50, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):27.

-

Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, do and policy. Wellness Educ Res. 1998;13(1):87–108.

-

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke 1000, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA argument for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate wellness care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;half-dozen(7):e1000100.

-

Viswanathan One thousand, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, Chang S, Hartling L, McPheeters M, Santaguida PL, Shamliyan T, Singh Thou, Tsertsvadze A. Assessing the risk of bias of individual studies in systematic reviews of health care interventions; 2012.

-

Song F, Hooper L, Loke Y. Publication bias: what is information technology? How practice we measure it? How practice nosotros avoid it? Open Access J Clin Trials. 2013;2013(5):71–81.

-

Qualtrics L. Qualtrics: online survey software & insight platform; 2014.

-

Inc S. SPSS Base 14.0 user's guide: Prentice Hall; 2005.

-

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger Grand, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;iv(10):e296.

-

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8(one):xviii.

-

Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, Straus SE. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):110.

-

LaPelle NR, Zapka J, Ockene JK. Sustainability of public wellness programs: the example of tobacco treatment services in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(viii):1363–9.

-

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health touch on of wellness promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Wellness. 1999;89(nine):1322–7.

-

August GJ, Bloomquist ML, Lee SS, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM. Can evidence-based prevention programs be sustained in community practice settings? The Early on Risers' avant-garde-stage effectiveness trial. Prev Sci. 2006;7(ii):151–65.

-

Blanchet Chiliad, James P. Tin can international health programmes be sustained after the cease of international funding: the example of middle care interventions in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):77.

-

Bail GR, Drake RE, Becker DR, Noel VA. The IPS learning community: a longitudinal study of sustainment, quality, and effect. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(8):864–ix.

-

Romani MET, Vanlerberghe V, Perez D, Lefevre P, Ceballos Eastward, Bandera D, Gil AB, Van der Stuyft P. Achieving sustainability of customs-based dengue control in Santiago de Cuba. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(iv):976–88.

-

Grow HMG, Hencz P, Verbovski MJ, Gregerson 50, Liu LL, Dossett L, Larison C, Saelens Exist. Partnering for success and sustainability in community-based child obesity intervention: seeking to help families ACT! Fam Community Health. 2014;37(ane):45–59.

-

Splett PL, Erickson CD, Belseth SB, Jensen C. Evaluation and sustainability of the good for you learners asthma initiative. J Sch Health. 2006;76(vi):276–82.

-

Lyon AR, Frazier SL, Mehta T, Atkins MS, Weisbach J. Easier said than done: intervention sustainability in an urban after-school programme. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38(vi):504–17.

-

Palinkas LA, Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Levine B, Garland AF, Hoagwood KE, Landsverk J. Continued use of prove-based treatments after a randomized controlled effectiveness trial: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(11):1110–8.

-

Bergmark M, Bejerholm U, Markström U. Implementation of testify-based interventions: analyzing critical components for sustainability in community mental health services. Soc Work Ment Health. 2019;17(2):129–48.

-

Smith ML, Durrett NK, Schneider EC, Byers IN, Shubert TE, Wilson Advertising, Towne SD Jr, Ory MG. Test of sustainability indicators for autumn prevention strategies in iii states. Eval Programme Plann. 2018;68:194–201.

-

Llauradó East, Aceves-Martins Thou, Tarro Fifty, Papell-Garcia I, Puiggròs F, Prades-Tena J, Kettner H, Arola Fifty, Giralt 1000, Solà R. The "Som la Pera" intervention: sustainability capacity evaluation of a peer-led social-marketing intervention to encourage healthy lifestyles among adolescents. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8(5):739–44.

-

Fagan AA, Hanson Thou, Briney JS, Hawkins JD. Sustaining the utilization and high quality implementation of tested and constructive prevention programs using the communities that care prevention arrangement. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;49(3–four):365–77.

-

Ahluwalia IB, Robinson D, Vallely L, Gieseker KE, Kabakama A. Sustainability of community-capacity to promote safer motherhood in northwestern Tanzania: what remains? Glob Health Promot. 2010;17(1):39–49.

-

Bradley EH, Webster TR, Bakery D, Schlesinger M, Inouye SK. After adoption: sustaining the innovation a case report of disseminating the hospital elderberry life program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(nine):1455–61.

-

Vamos Due south, Mumbi Chiliad, Cook R, Chitalu N, Weiss SM, Jones DL. Translation and sustainability of an HIV prevention intervention in Lusaka, Zambia. Transl Behav Med. 2013;4(2):141–eight.

-

Grouping WB. World development indicators 2014: World Bank Publications; 2014.

-

Roy-Byrne PP, Sherbourne CD, Craske MG, Stein MB, Katon W, Sullivan M, Means-Christensen A, Bystritsky A. Moving treatment enquiry from clinical trials to the real world. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(3):327–32.

-

Bradley EH, Webster TR, Bakery D, Schlesinger M, Inouye SK, Barth MC, Lapane KL, Lipson D, Stone R, Koren MJ. Translating inquiry into practice: speeding the adoption of innovative wellness care programs. Issue Cursory (Commonw Fund). 2004;724(1):12.

-

Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: awarding of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;two(1):42.

-

Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, Elliott MB, Herbers SH, Mueller NB, Bunger AC. Public wellness program chapters for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci. 2013;viii(1):1.

-

Gruen RL, Elliott JH, Nolan ML, Lawton PD, Parkhill A, McLaren CJ, Lavis JN. Sustainability science: an integrated arroyo for health-plan planning. Lancet. 2008;372(9649):1579–89.

-

Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of plan sustainability. Am J Eval. 2005;26(3):320–47.

-

Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ. A guiding framework and approach for implementation inquiry in substance employ disorders treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(ii):194.

-

Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM. Implementation inquiry: a synthesis of the literature; 2005.

-

McMichael C, Waters E, Volmink J. Evidence-based public wellness: what does it offer developing countries? J Public Health. 2005;27(2):215–21.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported past the National Institute of Minority Health and Wellness Disparities Middle grant U54MD011227 (PI: C. Debra Furr-Holden).

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

Advertizement drafted the systematic review protocol. MH and TB contributed to the protocol. MH and TB did the search, merged the information, removed the duplicates, and reviewed the championship and abstracts of the studies. MH, AD, LE, and TB did the initial full-text review. MH, Ad, TB, BM, and RB conducted the second round of the review and coding of the themes. MH drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed, contributed, and approved the last manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicative

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/one.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Most this article

Cite this commodity

Hailemariam, M., Bustos, T., Montgomery, B. et al. Testify-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 14, 57 (2019). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s13012-019-0910-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6

Keywords

- Sustainment

- Sustainability

- Evidence-based interventions

- Sustainment outcomes

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6

0 Response to "Review the Concept of Evidence-based Public Health Strategies"

Post a Comment